CGKB News and events Management strategies

Bacteria - rice

Contributers to this page: IRRI, Seed Health Unit, Los Banos, Philippines(Patria Gonzales, Evangeline Gonzales, Carlos Huelma, Myra Almodiel, Joel Dumlao).

|

Contents: |

Scientific names

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (ex Ishiyama) Swings et al.

Syn. X. campestris pv. oryzae (Ishiyama) Dye

Significance

Yield losses (10-50%).

Symptoms

Blight (starts as water-soaked stripes a few centimeters below the leaf tip, or on the margin of the leaf blade; these stripes enlarge and turn yellow within a few days).

“Kresek” or wilting.

“Pale yellow leaf".

Host range

Leersia sayanuka Ohwi; L. oryzoides (L.) Sw., L. japonica, Zizania latifolia (Griesb.)Turcz. ex Stapf., Leptochloa chinensis (L.) Nees, L. panacea (Retz.) Ohwi, L. filiformis , Cyperus rotundus L. and C. difformis.

Geographic distribution

Asia, Australia, Africa, Latin America, the Carribean, and United States of America.

Biology and transmission

Survives primarily in rice stubbles and alternate weed hosts enters the host through stomata, wounds, and other injuries to leaves, hydathodes, cracks at the base of the leaf sheaths.

Irrigated and rainfed lowland ecosystems support the disease development.

Heavy rains with strong winds facilitate disease development by causing wounds in plants.

Dry weather helps bacterial exudates fall into irrigation water, spread the disease to neighboring fields.

Moderately high temperatures (25°C-30°C) increase the disease incidence.

|

|

Excessive use of nitrogen especially organic N as late topdressing, phosphate, and K deficiency, excess silicate and Mg predispose plant to infection.

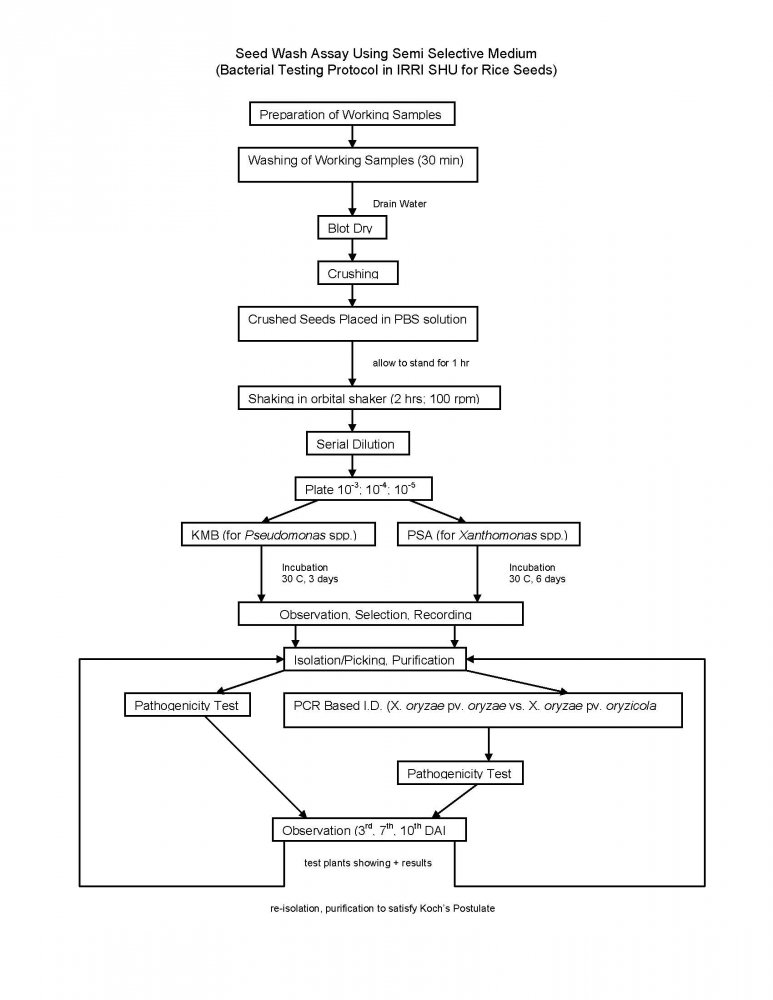

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Seed Wash Assay Test (using semi selective medium).

-

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP).

- Requires database to reference.

- Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP).

- Labor intensive and not efficient for diagnostics.

- Oligonucleotide arrays.

-

Macroarrays.

- Hybridize sample DNA to anchored pathogen.

- Specific oligos.

-

Antibody-based = Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA).

- Requires increased processing time and expenses.

Treatment/control

- The disease can be effectively controlled with resistant cultivars.

- Cultural control includes avoiding excessive N fertilization, maintaining shallow water in nursery beds, providing good drainage during severe flooding, plowing under of rice sybbles and straw following harvest, and removing alternate hosts.

- Control of disease with copper compounds, antibiotics, and other chemicals has not proven effective.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds found to be positive with the organism are deleted from shipments for export.

- Bacterial testing is not conducted on incoming rice seeds but shall be planted in post entry plant quarantine area only. Plants are closely monitored during its active growth. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing. IRRI.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS, editors. 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Scientific names

Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Fang et al) Swings et al.

syn. X. campestris pv. oryzicola (Fang et al) Dye; X. translucens f.sp. oryzicola

Significance

Yield losses estimated at 1-17% depending on cultivar and climatic condition.

Symptoms

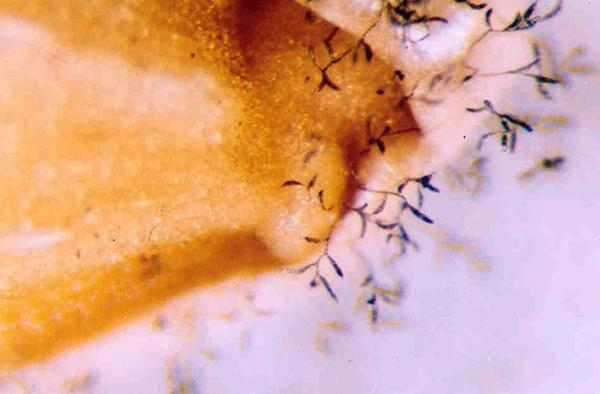

Translucent interveinal streaks (variable length on the leaf); old lesions become light brown.

Yellowish droplet of bacterial ooze on lesions under humid conditions; ooze look like beads under dry conditions.

Host range

All wild species of the genus Oryza can be infected and may serve as reservoirs of inoculum.

Geographic distribution

Widely distributed in Tropical Asia and in West Africa.

Biology and transmission

The bacterium survives largely on infected seed and straw; may also be able to survive in irrigation water.

The bacterium enters the host through stomates or wounds and multiplies in parechymatous tissue.

Bacterial exudates from leaf lesions are disseminated primarily by splashing and windblown rain, also by leaf contact and irrigation water.

Disease develops in both lowland and upland ecosystems.

Disease development is favored by rain, high humidity (more that 80%) and high temperature (more that 30°C).

Infected seeds and contaminated water can introduce the disease to new areas.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

|

- At IRRI – Seed Wash Assay Test (using semi selective medium).

-

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP).

- Requires database to reference.

-

Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP).

- Labor intensive and not efficient for diagnostics.

- Oligonucleotide arrays.

-

Macroarrays.

- Hybridize sample DNA to anchored pathogen.

- Specific oligos.

-

Antibody-based = Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA).

- Requires increased processing time and expenses.

Treatment/control

- The disease can be effectively controlled with resistant cultivars and the use of treated seeds.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds found to be positive with the organism are deleted from shipments for export.

- Bacterial testing is not conducted on incoming rice seeds but shall be planted in post entry plant quarantine area only. Plants are closely monitored during its active growth. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing. IRRI.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS, editors. 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Fungi - rice

Contributers to this page: IRRI, Seed Health Unit, Los Banos, Philippines(Patria Gonzales, Evangeline Gonzales, Carlos Huelma, Myra Almodiel, Joel Dumlao).

|

Contents: |

Scientific names

Pyricularia oryzae Cav.

syn. P. grisea (Cooke); Piricularia grisea; P. oryzae Cav. Dactylaria oryzae (Cav.) Sawada; Trichotecium griseum (Cooke)

teleomorph: Magnaporthe grisea (Hebert) Barr

Ceratospaeria grisea Hebert

Phragmoporthe grisea Hebert (Mood)

Significance

The disease is generally considered as the principal disease of rice because of its wide distribution and its destructiveness under favorable conditions causing crop failure and epidemics. The epidemic potential is very high under favorable conditions.

In Japan (1960) estimated yield loss was 273,300 tons; In India (1960-61) yield loss was more than 266,000 tons; In the Philippines, many thousands of hectares have suffered more than 50% losses in yield.

Symptoms

The fungus can infect rice plants at any growth stage although it is more frequent at the seedling and flowering stage.

On the leaves – initially, lesions appear as small whitish or grayish specks that eventually enlarge and become spindle-shaped necrotic spots with brown to reddish brown margins. The size, shape, and color of the spots vary depending upon the susceptibility of the variety and environmental conditions.

On the panicle base – infected tissue shrivels and turns black. It breaks easily at the neck and hangs down.

On the nodes – infected nodes rot and turn black.

|

|

Host range

Graminae – Eriochloa villosa, Eremochloa ophiuroides, Leersia japonica, L. hexandra, Panicum repens, Phragmites communis, Arundo donax, Brachiaria mutica, Stenotaphrum secundatum, Saccharum officinarum, Pennisetum typhoides

The Index of Plant Diseases in the United Sates (1952) listed the following plants as hosts: Agrostis, Andropogon, Digitaria, Eragrostis, Fluminea, Leersia, Muhlenbergia, Panicum, Paspalum, Sorgum spp. Cynodon dactylon, Hystrix patula Cistichlis, Eleusine indica, and Panicum ramosum.

Zingiberacea – Zingiber officinale, Z.mioga, Curcuma aromatica, Costus speciosus, Canna indica, Musa sapientum, Cyperus rotundus, C. compressus

Geographic distribution

Widely distributed in all rice growing countries. It is most prevalent in temperate subtropical environment and rice grown in upland conditions.

Biology and transmission

Conidia are produced and released during periods of high relative humidity, and daily production generally peaks between midnight and 0600 hr.

No sporulation occurs below 89% relative humidity, and sporulation increases with increasing relative humidity above 93%.

The optimum temperature for sporulation is 25-28°C.

The highest rate of spore production is attained 3-8 days after lesion appearance, and lesions maintain the ability to produce spores longer at 16-24°C than at 28°C.

Optimum temperature for spore germination is 25-28°C and for appressorium formation is 16-25°C.

The latent period required for lesion formation varies from 13-18 dyas at 9-11°C to an optimum of 4-5 days at 26-28°C.

Seedborne inoculum is an important source of primary infection where seed is sown densely in seedling boxes for mechanical transplanting.

The pathogen overseasons in infested crop residue or in seed in temperate regions where only one rice crop is sown per year.

Blast is favored by culture of rice in anaerobic soil or in wetlands where intermittent drought stress occurs, by N fertilization, by long duration of leaf wetness due to drizzle or dew deposition, by little or no wind at night, and by night temperatures between 17° and 23°C.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- In environments not highly conducive to blast, the disease can be easily controlled by planting resistant cultivars.

- In environments with high epidemic potential and where few resistant cultivars are available – combine host resistance with manipulating time of planting, fertilizer, and water management , and use of fungicides (such as pyroquilon and triclazole).

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds found to be positive with the organism are deleted from shipments for export.

- Imported seedlots found to be infected with the organism are treated with fungicides; closely monitored during active growth;

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds) 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Scientific names

Fusarium moniliforme Sheld.

syn. F. heterosporum Nees; F. verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg; Lisea fujikuroi Sawada

teleomorph: Giberella fujikuroi (Sawada)D. Ito; G. moniliformis Wineland; G. moniliforme

Significance

One of the first diseases of rice to be described scientifically

Responsible for yield losses of up to 50% in Asia

The disease can be observed in the seedbeds and in the field

Symptoms

Elongated, slender, and pale seedlings (classic symptom), but infected seedlings may also be stunted and chlorotic, exhibiting root and crown rot which eventually die.

Infected older plants exhibit abnormal elongation (tall and lanky tillers), have few tillers, and produce adventitious roots at the lower nodes and culm. Plants that survive until maturity do not produce panicles; if panicles are produced, the panicles are empty.

Leaf sheaths of infected plants may turn blue-black with the production of perithecia.

Panicles of healthy plants may be infected and turn pink, and the hulls or seeds may have a reddish color due to growth and sporulation of the fungus.

Host range

Maize, barley, sugarcane, sorghum, and Panicum miliaceum

Geographic distribution

Widely distributed in all rice growing countries. It is most prevalent in temperate subtropical environment and rice grown in upland conditions.

Biology and transmission

|

|

F. moniliforme is seedborne and primarily seed transmitted.

The fungus survives the winter (or summer in the tropics) in infected seeds and other parts of the diseased plants; may also survive in the soil in infested crop residue as thick walled hyphae or macroconidia, but is relatively short lived in the soil.

The fungus infects the plants through the roots or crowns and grows systemically in the plant but does not systemically infect the panicle.

The fungus maybe isolated from healthy looking seeds collected from an infested field.

Seeds are infected at the flowering stage via airborne ascospores and also from conidia that contaminate the seed during harvesting.

The disease is favored by high temperatures (30-35°C).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- Seed treatment such as Benomyl and benomyl-thiram combinations (at IRRI slurry treatment at 0.3% g /100 g of seeds).

- The use of clean seed is essential to control bakanae (At IRRI-moldy, discolored, partially filled/unfilled, shriveled/deformed seeds are removed during Dry Seed Inspection).

- Salt water can be used to separate lightweight, infected seeds, thereby reducing seedborne inoculum.

- The use of resistant cultivars.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds for export found to be positive with the organism are treated with recommended fungicides.

- Imported seedlots found to be infected with the organism are treated with fungicides; closely monitored during active growth;

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds) 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Brown spot (brown leaf spot or sesame leaf spot)

Scientific names

Bipolaris oryzae (Breda de Haan) Shoem.

syn. Drechslera oryzae (Breda de Haan) Subram. & Jain

Helminthosporium oryzae

teleomorph: Cochliobolus miyabeanus (Ito & Kurib)

Significance

The fungus causes seedling blight, necrotic spots on leaves and seeds, and also grain discoloration.

Infection of this disease results in reduction in number of grains per panicle and kernel weight.

Severely infected seeds may fail to germinate.

Seedling blight is common on rice in both rainfed lowlands and uplands. Under these rice production situations, brown spot can be a serious disease causing considerable yield loss. In history, an epidemic of the disease in Bengal in 1942 resulted in yield losses of 40-90% and was largely responsible for the Bengal famine of 1943.

Symptoms

On leaves – small and circular dark brown or purple brown spots eventually becoming oval (similar to shape and size of sesame seeds) and brown spots with gray to whitish centers, evenly distributed over the leaf surface; spots are much larger on susceptible cultivars. A halo relating to toxin produced by the pathogen often surrounds the lesions.

On glumes – black or brown spots covering the entire surface of the seed in severe cases. Under favorable environments, conidiophore and conidia may develop on the spots, giving a velvety appearance.

On coleoptile – small circular or oval brown spots.

Host range

|

|

Species of some 23 grass genera and 20 species of Oryza have been reported to be susceptible to infection by B. oryzae.

Zizania aquatica (L.), Leersia hexandra.

Geographic distribution

Brown spot is distributed worldwide and reported in all rice-growing countries in Asia, America, and Africa. It is more prevalent in rainfed lowlands and uplands or other situations with abnormal or poor soil conditions.

Biology and transmission

In temperate regions, the primary source of inoculum is infected and infested seed, but the fungus also overwinters in infected crop debris; however, diseased seeds do not necessarily always give rise to infected seedlings.

Reports show that conidia on infected grain can remain viable from 2-4 years.

In the tropics, seedborne inoculum is less important because inoculum is present year round in overlapping rice crops.

Infection can occur between 16 and 36°C; optimum temperatures are reported to lie between 20 to 30°C.

Infection is favored by free water on plant surfaces but infections have been reported to occur in situations without free water at relative humidities above 89%.

Water stress increases host susceptibility.

High and low levels of nitrogen have been reported to increase susceptibility of rice plants to the disease.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- The most important factors in the control of brown spot are proper nutrients in the soil and prevention of water stress.

- The use of resistant cultivars in areas where the disease is severe and associated soil abnormalities are not easily corrected.

- Chemical seed treatment has proven effective in reducing seedling blight caused by B. oryzae

- Seed treatment such as Benomyl and benomyl-thiram combinations (at IRRI slurry treatment at 0.3% g /100 g of seeds).

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds for export found to be positive with the organism are treated with recommended fungicides

- Imported seedlots found to be infected with the organism are treated with fungicides; closely monitored during active growth;

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds) 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Scientific names

Sarocladium oryzae (Sawada) W. Gams & D. Hawks.

syn. S. attenuatum W. Gams & D. Hawks; Acrocylindrium oryzae Sawada Hebert

Significance

The disease has commonly caused yield losses of 20-85%.

Symptoms

Lesions start at the uppermost leaf sheath enclosing young panicles as oblong or irregular spots with brown margins and gray center or brownish gray throughout. Spots enlarge and coalesce covering most of the leaf sheath. Panicles remain within the sheath or may partially emerge.

Panicles that have not emerged tend to rot, and florets turn red-brown to dark brown.

Seeds associated with this disease are sterile, shriveled or partially filled.

Affected leaf sheaths have abundant whitish powdery mycelium.

|

|

Host range

Several weed hosts, bamboo.

Geographic distribution

The fungus is present in all rice growing countries worldwide

The disease has become more prevalent in recent decades and is very common in rainfed rice or rice during rainy season

Biology and transmission

The fungus survives as mycelium in infected residue and on seeds.

The fungus invades rice through the stomata and wounds and grows intercellularly in the vascular bundles and mesophyl tissues.

Insect damage especially from stem borers, mites, and lealy bugs, aids disease development by retarding panicle emergence and causing entry wounds for the fungus.

The disease appears to be favored by low nitrogen levels or dense stands

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- The use of resistant cultivars.

- The use of clean seeds as planting materials (sterile, shriveled or partially filled seeds is essential in the control of this disease).

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds for export found to be positive with the organism are treated with recommended fungicides.

- Imported seedlots found to be infected with the organism are treated with fungicides; closely monitored during active growth;

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds) 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Scientific names

Microdochium oryzae (Hashioka & Yokogi) Samuels & Hallett

syn. Gerlachia oryzae (Hashioka & Yokogi) W. Gams.

Rhychosporiu oryzae Hashiola & Yokogi

Significance

Considered a relatively minor problem causing little yield loss in rice production.

Symptoms

Characteristic symptoms on mature leaves include zonated lesions that start on leaf tips or edges.

Lesions are more or less oblong with light brown halos, 1-5 cm long, 0.5-1 cm broad.

Individual lesions enlarge and eventually coalesce.

Zonation on the old lesions fades.

Host range

Echichloa crusgalli

Geographic distribution

Leaf scald appears to be very common in Latin America and in other parts of Asia.

It has been reported in USA and West Africa.

|

Leaf Scald |

Biology and transmission

Conidia inoculated on rice leaves fuse together or connected to each other by germ tubes forming conidial complex; vigorous hyphae are then produced.

Hyphae enters through the stomata after which appresorium-like structures of various sizes are formed; from these structures, infection hypahe developes, passing through stomatal slits and swelling in substomatal cavities.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- The use of resistant cultivars

- The use of clean seeds as planting materials (sterile, shriveled or partially filled seeds is essential in the control of this disease)

- Increasing the amount of nitrogenous fertilizer favours the disease.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

- Seeds for export found to be positive with the organism are treated with recommended fungicides

- Imported seedlots found to be infected with the organism are treated with fungicides; closely monitored during active growth;

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds). 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Scientific names

Tilletia barclayana (Bref.) Sacc. & Syd.

syn. Neovossia barclayana Bref.

T. horridaTak.

N. horrida (Tak.) Padw. & Kahn

Significance

The disease can be observed in the field at the mature stage of the rice plant. It is considered economically important, causing stunting of seedlings and reduction in tillers and yield when smutted seeds are planted. Yield losses as high as 15% have been reported.

Symptoms

The disease is found in the field at the time of maturity of the rice crop.

The disease is most noticeable early in the morning when dew causes completely smutted grains to swell and erupt. Sometimes, infected grains may be detected by their dull color.

Ordinarily, affected plants have on a few smutted grains, which appear at random positions in the panicle.

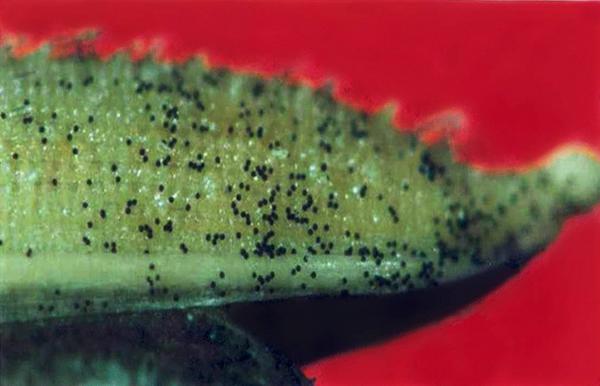

Infected grains may be completely or partially infected. When completely infected, the endosperm is replaced with a black, sooty mass of spores (often termed as chlamydospores)

Infected grains show minute, black pustules or streaks bursting through the glumes. In severe cases, a short beak-like or spur-like outgrowth is produced by the rupturing glumes

Host range

Oryza barthii, Brachiaria sp., Digitaria sp., Eriochlora sp., Panicum sp., and Pennisetum sp.

Geographic distribution

The disease is known to occur in many countries worldwide – Japan, United States, India, Burma, China, Philippines, Taiwan, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Mexico, Guyana, Trinidad, Brazil, Venezuela, Panama, and Sierra Leonne

Biology and transmission

Chlamydospores live for a year or more under normal conditions and have been found to be viable after three (3) years in stored grains.

Healthy kernels, crop debris, and soil are contaminated by chlamydospores which are released from completely smutted grains before or during harvest.

|

|

Chlamydospores float to the surface of the paddy water and germinate to form primary sporidia. These primary sporidia are released from the promycelim and form secondary sporidia in great numbers, either directly or from mycelium produced by the primary sporidia. Secondary sporidia are forcibly discharged into the air and disseminated to rice panicles by air currents. The secondary sporidia can infect the developing ovaries if the florets are open.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Blotter Test (Annexe 7.4.3.a.7 of the ISTA Rules (2008)

Treatment/control

- Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) seed washing treatment.

- Germination of some rice varieties maybe adversely affected, thus, it is best to plant seeds immediately after treatment.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

General Protocol:

- If contamination/infection on grains is <10%, seedlot is “cleaned” – under the stereo microscope, grains with kernel smut are manually removed

- If contamination/infection on grains is >10%, seedlot is either treated with 1% sodium hypochlorite, deleted/rejected, or replaced, depending upon the country of destination

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area only. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service.

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing.

Mew TW, Gonzales PG. 2002. A Handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS. (eds). 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Nematodes - rice

Contributers to this page: IRRI, Seed Health Unit, Los Banos, Philippines(Patria Gonzales, Evangeline Gonzales, Carlos Huelma, Myra Almodiel, Joel Dumlao).

White tip

Scientific names

Aphelenchoides besseyi Christie

Significance

Yield of infected plants is lost or reduced but yield lost or reduction vary depending on cultivar, year, temperature, and cultural practices

According to reports, average yield losses in infested fields ranged from 10-30%;in fields where all plants (most susceptible cultivars) have been attacked, yield losses were up to 70%

Severity of the disease is increased by Ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, calcium superphosphate, and potassium chloride.

Symptoms

Whitening of 3-5 cm of the leaf tip which eventually become necrotic and shred (typical symptom). The central part and the base of the infected leaves are darker green than normal. The upper leaves are the most affected, with the flag leaf often twisted, hindering the emergence of the panicle.

Other symptoms-reduced panicle length, reduced number of grains, sterile flowers, deformed grains, stunted plants, late ripening and maturation of grains, production of tillers in the upper nodes

Not all plant infected with A. besseyi show the white tip symptom although the yields are reduced

Host range

Setaria viridis (foxtail), Panicum sanguinale (crab grass), Cyperus iria, Cyperus polystachyus, Imperata cylindrical

|

|

Also known to occur in millet, strawberry, Vanda orchids, chrysanthemum, saintpaulia, Chinese cabbage, onion, soybean, sugarcane, sweet corn, sweet potato, yam, and more than 35 genera of higher plants and many species of fungi (Fortuner & Williams (1975)

Geographic distribution

White tip has been reported in most of the rice-growing countries of Africa, North, Central, and South America, Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Pacific.

Biology and transmission

A. besseyi parasitizes flooded and upland rice. This nematode survives from one season to the next in infected seeds; can survive in seeds in a dehydrated state up to 3 years; can also survive to a lesser extent on weeds, on ratoons, and debris from the preceeding rice crop.

Reviviscent nematodes that emerge from the seeds after planting are attracted by and feed on the primordial of emerging plants, later moving to the growing points of the stem and leaves feeding ectoparasitically. The nematode multiplies abundantly and is carried upward as the plant grows. The nematodes eventually migrate to the developing panicle, punctures the inflorescence, and penetrates into the florets via the apicular opening, where it feeds (on the ovaries, stamens, and embryos) and reproduces. After anthesis, reproduction declines and ceases in maturing grains, becoming dormant as the grains dehydrate.

The nematode is inactive if the atmospheric humidity is less than70% and migrates on aerial plant parts when they are covered with a film of water. The optimum temperature for development is 23-32°C but the nematode is active from 13-43°C. The nematode is killed at temperatures exceeding 43°C.

The nematode is effectively spread by irrigation water.

A. besseyi is amphimictic, but parthenogenetic reproduction may occur; life cycle takes 7-15 days depending on temperature and humidity; there are several generations during a growing season

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center

- At IRRI – Modified Baermann Funnel Method (Sedimentation Test)

Treatment/control

- Hot-water treatment of infected rice grains (52-57°C for 15 minutes; for large volumes of seeds, presoaking in cold water for 3 hrs, then, the hot water treatment). The treated seeds are re dried back to recommended 14 % MC Germination of some rice varieties maybe adversely affected, thus, it is best to plant seeds immediately after treatment.

Procedure followed at the centers in case of positive test

General Protocol:

- Seedlots positive with Aphelenchoides besseyi are subject to deletion, replacement, or hot water treatment taking into account the import regulations of country of destination

Note: All imported seedlots are planted in IRRI’s post entry plant quarantine area only. Plants showing disease symptoms are immediately destroyed and disposed according to the recommendation of the Philippine Plant Quarantine Service

References and further reading

Ou SH. 1985. Rice Diseases 2nd ed. The Commonwealth Mycological Institute. UK

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A Manual of Rice Seed Health Testing. IRRI.

Webster RK, Gunnel PS, editors. 1992. Compendium of Rice Diseases. The American Phytopathological Society. USA

Best practices for the safe transfer of rice germplasm

Contributers to this page: IRRI, Seed Health Unit, Los Banos, Philippines(Patria Gonzales, Evangeline Gonzales, Carlos Huelma, Myra Almodiel, Joel Dumlao).

The best practices in place at IRRI are summarized for key aspects related to the Seed Health Unit in this section.Preventing the introduction of diseases, weeds, and any potential pest to areas where these biological hazards are not present, is the primary function of any plant quarantine office of that location. General Guidelines for Importation, Use and Handling Wild Rice Seeds and/or Vegetative Parts are in place at IRRI.

Routine Seed Health Testing (RSHT) Quality and Quantity Standards include Blotter Test, Nematode Test, Macro Test/Tb cleaning, Documentation, Washing, Germination Test. Technical details on routine seed health testing procedures are provided.

|

ACTIVITY |

STANDARD QUANTITY (min qty/hr) |

STANDARD QUALITY |

|

1. Blotter Test a. Seeding

b. Evaluation

|

61-70 plates

Not Treated- 51-60 plates Treated -61-70 plates |

according to ISTA rules & standards (25 seeds/plate; readable/ correct labels; w/ 2 layers of moist blotter paper; seeds equidistant from one another & properly oriented

Accurate identification of seedborne organisms - no missed/misidentified organism in 99% plates evaluated; timely evaluation – 5 to 7 days after incubation. |

|

2. Nematode Test a. Setting/extraction

|

81-90 samples

51-65 samples |

correct weight of samples, correct amount of water (seeds are covered) germinated seeds are properly spread over the mesh wire, no seeds in the tygon tubing, pinchcock properly placed-no leakage, spillage of water/ seeds accurate identification (+/-; saprophytic or parasitic) and actual count (if parasitic) evaluation conducted as soon as extracts are gathered |

|

3. Macro Test/Tb cleaning |

1.1-1.5 K |

correct evaluation (+/-) of Tilletia barclayana |

|

4. Documentation |

181-200 samples |

data/info complete & accurate; manner (no erasures, readable) in which data is recorded generally good; immediately done after evaluation (consistency - 99% of the time) |

|

5. Washing |

241-260 plates; 76-85 funnels; 101-120 wire mesh

|

no pencil marks, water marks, fungal growth; thoroughly dried |

|

6. Germination Test

a. Seeding

b. Evaluation |

41-45 seedlots

|

correct number of seeds-100/tray; correct orientation of seeds, moisture of blotters, correct labelling;

timely with regards to evaluation (5 DAS, 7DAS, & 14 DAS); correct evaluation as to Normal/Abnormal seedlings, dead seeds (in accordance to ISTA Rules and Standards in Seedling Evaluation) |

At IRRI SHU, methods for the detection of fungal pathogens include: seed washing technique, blotter test, potato dextrose agar (PDA) method and the oatmeal agar method.

Methods for detection of fungal pathogens

1. Seed washing technique

This is useful in testing surface-borne, contaminating fungi like smuts, bunts, downy mildews, powdery mildews, rusts, etc.

Procedure

1. Place two grams of seed sample in a test tube and mix it well by adding 2 ml of sterile water for 5-10 minutes.

2. Centrifuge the supernatant solution at 200 rpm for 10 minutes and observe the sediments under a microscope for fungal structures.

2. Blotter test

Procedure

1. Line the lower lid of sterilized petri dishes with three layers of absorbent paper moistened with sterile water.

2. Drain off excess water and place 20–25 seeds manually with a forceps.

3. Evenly space the seeds to avoid contact with each other.

4. Incubate the seeds under near ultraviolet light in alternating cycles of 12-h light/darkness for 7 d at 20 + 2°C.

5. Examine the petri dishes under a stereo-binocular microscope for fungi developing on the seeds.

Profuse seedling growth may make interpretations difficult. This may be overcome by adding 2,4-D sodium salt to provide a 0.2% moistening solution.

3. Potato dextrose agar (PDA) method

Procedure

1. Prepare the medium by mixing 1 gram of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) powder in 100 ml of distilled water.

2. Sterilize the mixture in an autoclave for 15–20 min and cool to about 50°C.

3. Carefully pour the mixture into sterile petri dishes by lifting the lid enough only to pour in the agar to avoid contamination.

4. Allow it to cool and solidify for 20 min.

5. Surface-disinfect the seed by pretreating for 1 min in a 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution prepared by diluting 20 parts of laundry bleach (5.25% NaOCl) with 85 parts of water.

6. Place about 10 seeds (depending on size) on the agar surface with a forceps.

7. Incubate the petri dishes at 20–25°C for about 5–8 days.

8. Identify the seedborne pathogens on the basis of colony and spore characteristics.

Near ultraviolet light with a wavelength 300-380 nm (also called black light) may be required to promote sporulation.

Some times bacterial colonies develop on the agar and inhibit fungal growth making identification difficult. This can be overcome by adding an antibiotic such as streptomycin (500 ppm) to the autoclaved agar medium after it cools to 50–55°C.

4. Oatmeal agar method

Procedure

1. Prepare the medium by mixing 10 gram of ground oatmeal powder with 10g of pure agar in 1l of distilled water.

2. Warm on a stirrer hotplate mixing continuously until the agar has melted.

3. Sterilize the mixture in an autoclave at 220°C for 20 min and cool to about 50°C.

4. Mix in 4ml of tetracycline antibiotic solution (0.25g in 100ml) in one litre of media.

5. Carefully pour the mixture into sterile petri dishes by lifting the lid enough only to pour in the agar to avoid contamination.

6. Allow it to cool and solidify for 20 min.

7. Surface-disinfect the seed by pretreating for 1 min in a 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution prepared by diluting 20 parts of laundry bleach (5.25% NaOCl) with 85 parts of water.

8. Place about 10 seeds (depending on size) on the agar surface with a forceps.

9. Incubate the petri dishes at 20–25°C for about 10 days.

10. Identify the seedborne pathogens on the basis of colony and spore characteristics

Near ultraviolet light with a wavelength 300-380 nm (also called black light) may be required to promote sporulation.

The Bacterial Testing Protocol consist of a seed wash assay presented below:

General seed treatment in place at SHU include: Seed fumigation, hot water treatment of rice seed, slurry treatment with benomyl and mancozeb, sodium hypochlorite seed washing and crop health monitoring.

References and further reading

Mew TW, Misra JK. 1994. A manual of Rice Seed Health Testing. IRRI, Manila, The Philippines, 114,pp.

Mew TW, Gonzales P. 2002. A handbook of Rice Seedborne Fungi. Los Baños (Philippines): IRRI, and Enfield N.H.(USA) Science Publishers Inc. 83 pp. [online] Available from URL:http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org Date accessed 07 April 2010

More Articles...

Subcategories

-

main

- Article Count:

- 11

-

Stog

- Article Count:

- 2

-

Stog-rice

- Article Count:

- 7

-

Stog-sorghum

- Article Count:

- 11

-

Stog-common-bean

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-forage-legume

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-forage-grass

- Article Count:

- 11

-

stog-maize

- Article Count:

- 9

-

stog-chickpea

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-millets

- Article Count:

- 12

-

stog-barley

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-groundnut

- Article Count:

- 9

-

stog-pigeon-pea

- Article Count:

- 8

-

stog-wheat

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-lentil

- Article Count:

- 9

-

stog-cowpea

- Article Count:

- 10

-

stog-faba-bean

- Article Count:

- 9

-

risk management

- Article Count:

- 4

-

decision support tool

- Article Count:

- 3

-

stog-clonal

- Article Count:

- 23

-

developing strategies

- Article Count:

- 4