CGKB News and events Management strategies

Viruses - barley

Contributors to this section: ICARDA, Syria (Siham Asaad, Abdulrahman Moukahal).

|

Contents: |

Barley Stripe Mosaic Virus (BSMV)

Other scientific names

Barley False Stripe Virus, Possibly Barley Yellow Stripe Virus, Barley Mild Stripe Virus, Oat Stripe Mosaic Virus.

Disease name

Barley Stripe Mosaic.

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

Yield losses are proportional to the level of infection in the seed lot. Heavily infected crops have had yield reductions of up to 25%. The percentage of infected seedlings indicates the level of grain infection.

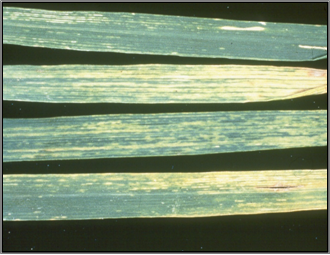

Symptoms

Yellow to white mosaic, spotting and necrotic stripes.

BSMV on the right (source: Bugwood.org) |

Hosts

Natural hosts are members of the Gramineae, but species of Chenopodiaceae and Solanaceae can be experimentally infected.

Geographic distribution

ASIA: Israel, Japan, Jordan, Pakistan; AUSTRALASIA and OCEANIA: Australia (Victoria), EUROPE: Bosnia & Herzegovina, Britain (England), Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Kosovo, Macedonia (FYR), Montenegro, Norway, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovenia; NORTH AMERICA: Canada, USA; SOUTH AMERICA: Argentina.

Biology and transmission

Transmitted by means not involving a vector. Virus transmitted by mechanical inoculation; transmitted by seed (up to 90-100%); transmitted by pollen to the pollinated plant.

The virus is seedborne and is transferred from plant to plant when the crop leaves rub against one another. Experimentally the virus can be transmitted by pollen, but since barley is self-pollinated this method of spread is generally of no consequence. Infected seeds produce infected plants. Seed from virus-infected plants is generally infected to a 60% level.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), (TBIA) Tissue Blot ImmunoAssay test.

Treatment

- Avoid introducing the disease.

- Use virus-free seed.

- Control volunteer barley. Do not plant barley after barley if the previous barley crop was infected.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive testing at ICARDA

- The seed lot is destroyed.

Significance

Not significant.

Symptoms

The Barley Mosaic Viruses are usually first noticed in the winter or early spring as yellow patches in the crop. They causes mosaic and stunting.

BMV typical symptoms on younger leaves (photo: rothamsted.ac.uk) |

Hosts

Avena sativa, Hordeum vulgare, Triticum aestivum.

Geographic distribution

India and Japan.

Biology and transmission

Virus is transmitted by aphids: Rhopalosiphum maidis and by mechanical inoculation; transmitted by seeds.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Centres

- At ICARDA - Not important.

Treatment/control

- Clean the seed. Barley Mosaic Viruses can be effectively controlled using resistant varieties.

References and further reading

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/ICTVdB/00.079.0.70.003.htm

http://www.apsnet.org/online/common/names/barley.asp

http://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/ppi/staff/mja.html

Seed Health General Publication published by the Centre or the CGIAR.

Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus (WSMV)

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

Early widespread infection of young wheat plants (approaching 100% infection) is generally associated with greatest yield losses from Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus (WSMV) and can cause complete crop failure, as such crops produce only small amounts of shrivelled grain. Patchy, early infection can also cause substantial yield losses within the affected crop area.

Symptoms

The symptoms of WSMV in wheat appear as pale green streaking on leaves, yellowing of the older leaves (especially towards their tips) and stunted, tufted plant growth. Affected plants become stunted compared to healthy plants when they are infected at an early growth stage (pre-tillering) but this stunting symptom is much less obvious with later infection. Heads on early infected, stunted plants are either sterile and contain no seed, or contain small shrivelled grain. Except for volunteer oats, no symptoms have been seen in Western Australia on WSMV-infected alternative hosts (grasses and barley).

Yellowing of the older leaves (photo: coopext.colostate.edu) |

Hosts

Avena sativa, Hordeum vulgare, Poa compressa, Secale cereale, Triticum aestivum and Zea mays.

Geographic distribution

The virus occurs in the Canada, United States, Jordan, Eastern Europe and Russian Federation.

Biology and transmission

Infections first appear at the margins of a field because of the movement of the virus's mite vector. Infections may occur in the winter, but symptoms often do not appear until the spring temperatures rise to above 10°C.

Transmitted by a vector; a mite; wheat curl mite (WCM) Aceria tulipae; Eriophyidae. The virus is not transmitted congenitally to the progeny of the vector; transmitted by mechanical inoculation; not transmitted by contact between plants; transmitted by seed (very low levels).

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Centers

- At ICARDA - Not significant.

Treatment

- Serious outbreaks of WSMV can only occur if the mite vector, WCM, is abundant and a source of WSMV is present. Consequently, management of the disease is highly dependent on controlling WCM populations and sources of WSMV. The control options available against WSMV include the following:

- Control the ‘green bridge’ (volunteer crop cereals e.g. wheat, barley, cereal rye, oats and grass weeds) as they harbour both WSMV and WCM. This control needs to be done throughout the paddock (including along the fence line) at least one month before sowing wheat. It needs to be very thorough, involving grazing down to ground level throughout the paddock and early application of herbicide. Neighbouring paddocks should be treated similarly, especially those upwind of the crop. Use of a glyphosphate/araquat mixture provides the most effective control.

- Sow healthy seed stocks of wheat (deemed healthy after seed testing of a representative seed ample).

- Avoid early sowing in virus risk conditions i.e. Sowing directly into a recently sprayed out ‘green bridge’ or sowing of infected seed, as warm seasonal conditions in autumn favour high WCM populations.

Procedure in case of positive test

Not applicable.

References and further reading

http://wheatdoctor.cimmyt.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=186&Itemid=43

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Tritici/Tritici_Wheat_streak_mosaic_rymovirus/

http://www.coopext.colostate.edu/TRA/Agronomy/HighPlains/hpd.figure2.jpg

http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/research/updates/issues/july-2006/wsmv-under-scrutiny

Bacteria - barley

Contributors to this section: ICARDA, Syria (Siham Asaad, Abdulrahman Moukahal).

|

Contents: |

Bacterial Leaf Streak, Bacterial Stripe, Xanthomonas Streak, Black Chaff

Scientific name

Xanthomonas translucens pv. translucens (ex Jones et al.) Vauterin et al.

Other scientific names

Xanthomonas campestris pv. translucens (Jones et al.) Dye

Xanthomonas translucens (Jones, Johnson and Reddy) Dowson

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

This disease can reduce barley yield by 5-90% depending on the zone of this culture and on favourable weather conditions for the development of the pathogen of bacteriosis. Yield losses may reach 13-34% at 50% affection of surface of flag leaf of barley, depending on susceptibility of varieties and climatic conditions.

Symptoms

Bacteriosis attacks leaves, stems and ears. At the first stage of disease development, small oblong aqueous, translucent spots of light green colour appear on the leaves. Then these spots expand and turn yellow to brown, even black. Sticky slime (exudate) is observed on spots, forming a yellowish film at drying. Leaves may die off at strong affection. Black or brown stripes are formed on stems. Stem below ear is sometimes completely brown. Blacking occurs on distal part of ear scales, later brown lateral stripes appear along the scales. Strongly diseased plants form no ears. Affected plants give only puny grain with yellow stripes.

Bacterial Leaf Streak (source: www.eppo.org) |

Hosts

The main hosts of X. translucens pv. translucens are barley (Hordeum vulgare), rye (Secale cereale), wheat (Triticum spp.) and triticale (Triticum x Secale). It has also been recorded on some grasses (Bromus spp., Phalaris spp., Elymus repens) and on other Poaceae by inoculation.

Geographic distribution

Worldwide.

Biology and transmission

X. translucens pv. translucens is a seedborne pathogen. The transmission rate is very low, but ensures serious outbreaks in the field under suitable conditions. The pathogen is disseminated by seed on a large scale (Sands and Fourest, 1989). On a local scale, bacteria are transmitted by rain, dew and contact between plants. Aphids trapped in sticky exudates may carry the bacterium and transmit it to wheat and barley, thus helping long-distance dissemination. Milus and Mirlohi (1995) concluded that other means of overwintering were insignificant compared to survival of the seed.

It is a true parenchymatous pathogen. Intercellular invasion occurs after entry through stomata. The spread from a single plant can affect up to 30 square metres during a growing season. However, movement in space is usually more limited. Infection cycles can be as short as ten days. Bacteria may survive in seeds for longer than 63 months. However, recovery is greatly decreased after some months of storage. Survival in the field does not solely dependent on the infection of host plants, as epiphytic populations may survive on non-host species. Moreover, bacteria may overwinter on perennial hosts, or on crop debris in the soil. Outbreaks of the disease are sporadic and more frequent on breeders' plots. They are prevalent during wet seasons. Inoculation experiments (Sands et al., 1986) show that plants are most readily infected under wet conditions (rain or sprinkler irrigation). However, the importance of dew, rainfall or irrigation has not yet been documented and it is not certain whether free water is needed. The bacterium tolerates a wide range of temperatures (15-30°C), its optimal temperature being around 22°C. The pathogen grows best when relative humidity is high. The disease is favoured by warm, moist conditions (26-30%), especially at heading.

The bacterium has ice-nucleating activity, and may therefore be associated with frost injury. Dissemination of the bacterium may in turn be favoured by this injury, since symptoms tend to appear after periods of sub-freezing temperatures. However, ice nucleation is not a necessary condition for induction of an epidemic.

Strains of X. translucens pv. translucens have been found to be host-specific, and the original formae speciales, later pathovars, were defined in this way: hordei (= translucens) on barley, secalis on rye, undulosa on wheat and triticale. Pv. cerealis had a relatively wide host range. Duveiller (1989) noted that isolates from wheat, rye and triticale were not host-specific. The fact that specific and non-specific strains can be found tends to support the use of a broad concept of the pathovar.

The bacteria are locally splash-dispersed over short distances. The only likely pathway for international spread is with infected seed lots.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Xts agar test, IN test.

Treatment/control

No known control measures exist for the disease in the field. Chemical control focuses on seed treatments. The recent resurgence of the disease has been linked with the withdrawal of this group of pesticides. However, Duveiller (1994) queries this and attributes the recent development to other causes: cultivation of cereals in new areas, favourable conditions for the disease, susceptible cultivars, etc. Various other treatments are now applied to seed lots to eliminate the bacterium, especially cupric acetate, formalin and guazatine, but these treatments are phytotoxic. Panoctine 30 was 95% effective and without phytotoxicity. Resistant cultivars are available for many cereals, the level of resistance depending on the cereal involved. In the absence of any really effective seed treatment, control should centre on pathogen-free seed certification.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test results

- Heat treatment 75°C for five days.

References and further reading

http://www.cabicompendium.org/NamesLists/CPC/Full/XANTTR.htm

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Tritici/Tritici_Xanthomonas_campestris_pv_translucens/

http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y4011E/y4011e0n.htm

http://www.eppo.org/QUARANTINE/bacteria/Xanthomonas_translucens/XANTTR_ds.pdf

http://www.cimmyt.org/research/wheat/bacterdismanag/pdf/BactDisMn-Chapter%202.pdf

Scientific name

Pseudomonas syringae pv. atrofaciens (McCulloch 1920) Young et al. 1978.

Other scientific name

Pseudomonas atrofaciens.

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

Yield losses due to poor seed fill have been reported. The status of the pathogen in the Ukraine is attracting considerable research attention.

Symptoms

The leaves, culms and spikes of wheat and triticale can be infected. Infections begin as small, dark green, water-soaked lesions that turn dark brown to blackish in colour. On the spikelets, lesions generally start at the base of the glume and may eventually extend over the entire glume. Diseased glumes have a translucent appearance when held toward the light. Dark brown to black discoloration occurs with age. The disease may spread to the rachis and lesions may also develop on the kernels. Under wet or humid conditions, a whitish grey bacterial ooze may be present. Stem infections result in dark discoloration of the stem; leaf infections result in small, irregular, water-soaked lesions. Symptoms can be confused with those of other bacterial diseases, septoria blotch and frost damage. The disease is transferred with seeds; at strong lesion, the seeds decay in the ground or seedlings die off.

Hosts

Wheat, barley, oat and rye.

Geographic distribution

Worldwide.

Biology and transmission

Pathogen remains in infected seeds and vegetation residues; it quickly perishes in the ground and it is seedborne.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Centres

- At ICARDA - King’s Medium B.

Treatment/control

- No satisfactory control; crop rotation and burying infected stubble are of limited value. Avoid seed from infected fields. Not controlled by foliar fungicides.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test results

- Producing healthy seed under controlled conditions.

References and further reading

Duveiller, E. 1994. Bacterial leaf streak or black chaff of cereals. Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin 24:135-158.

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/crops/pp533w-2.htm

http://scarab.msu.montana.edu/Disease/DiseaseGuidehtml/webpiclist.htm

http://www.bioversityinternational.org/fileadmin/bioversity/publications/pdfs/250.pdf

Nyvall RF. 1999. Field Crop Diseases. Basal Glume of Barley. [online]

Fungi (barley)

Contributors to this section: ICARDA, Syria (Siham Asaad; Abdulrahman Moukahal).

Barley Stripe, Barley Leaf Stripe, Helminthosporium Stripe

Scientific name

Pyrenophora graminea Ito & Kuribayashi.

Drechslera graminea (Rabenh.) Shoemaker [anamorph].

Other scientific name

Helminthosporium gramineum (Rabenh. ex Schltdl).

Importance

Seed transmitted.

Significance

Can strongly reduce germination and cause yield loss.

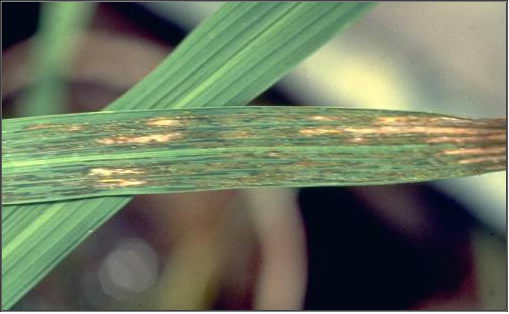

Symptoms

First symptoms appear on the second or third leaf of seedlings and on all leaves produced thereafter. Newly developed leaves have yellow stripes, particularly on the leaf sheath and on the basal portion of leaf blade. The stripes gradually extend along the full leaf length and soon become necrotic. Infected plants are usually stunted. Flag leaves are often light tan at the time of heading. In many infected plants, spikes are undeveloped or strongly shriveled, often being brown, but sometimes the grain may develop almost normally and exhibit little or no brown discoloration. The variation in symptoms is related to pathogen virulence and host resistance.

|

|

|

|

Barley Stripe (source: INRA) |

||

Hosts

Barley and other Hordeum spp. Also, occasionally, on oats, wheat and rye.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

Sporulation occurs on infected leaves under conditions of high moisture. About 16 hrs is required for conidia to mature at 12°C. Free water is not necessary for infection, which can occur at temperatures between 10 and 33°C. Incubation period is 6-9 days at temperatures from 18 to 22°C and humidity 70-85%. The maximum numbers of seedlings become infected when soil temperatures are below 12°C. Infection is reduced or prevented at temperatures above 15°C. More infection occurs when the relative humidity is near 100%, at temperatures from 15 to 25°C, with an optimum at about 22°C. Infection of barley leaves is greatest when humid conditions persist for 10-30 hrs or longer.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Cold blotter test, freezing blotter test (Asaad and El-Ahmed, 1999).

Treatment/control

- Treat seed with seed protectant fungicides. Resistant cultivars.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

Asaad S, El-Ahmed A. 1999. Improved method for detection of Pyrenophora graminea in barley seeds. Phytopathol Mediterr. 38:144-148.

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Pyrenophora_graminea/

http://www.cababstractsplus.org/abstracts/Abstract.aspx?AcNo=20056400388

http://www.inra.fr/hyp3/pathogene/6pyrgra.htm

Scientific names

Pyrenophora teres f.sp. teres Drechsler.

Drechslera teres f.sp. maculata Smedeg. [spot form]

Drechslera teres (Sacc.) Shoemaker [anamorph].

Other scientific name

Helminthosporium teres Sacc.

Importance

Seedborne incidence moderate. Economic importance low.

Significance

Net Blotch can cause a significant increase in screenings leading to downgrading from malting quality, as well as reduced yields. Of the two diseases, the Net form of Net Blotch (NFNB) is less prevalent, but potentially more damaging. Yield losses from NFNB generally range between 10 and 20%, but losses over 30% have been reported. Spot form Net Blotch (SFNB), although common early in the season, rarely develops sufficiently in spring to cause significant yield loss. Yield losses from SFNB generally range between 0 and 10%, but in severe outbreaks can exceed 20%.

Symptoms

Spot form of Net Blotch (SFNB): Symptoms are most commonly found on leaves, but occasionally also infect leaf sheaths. They develop as small circular or elliptical dark brown spots becoming surrounded by a chlorotic zone of varying width. These spots do not elongate to the net-like pattern characteristic of the Net form. The spots may grow to 3-6 mm in diameter. Older leaves will generally have a larger number of spots than younger leaves.

Net form of Net Blotch (NFNB): The Net form of Net Blotch starts as pinpoint brown lesions, which elongate and produce fine, dark brown streaks along and across the leaf blades, creating a distinctive net-like pattern. Older lesions continue to elongate along leaf veins, and often are surrounded by a yellow margin.

Net form of Net Blotch (source: NDSU, USA) |

Hosts

Barley and other Hordeum spp. Also, occasionally, on oats, wheat and rye.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

The main source of primary inoculum or initial crop infection comes from infected stubble. However, humid conditions while the crop is maturing may allow NFNB to infect seed, leading to infected crops the following year. Seed infection of SFNB is not regarded as an important source of primary inoculum.

The pathogen can survive for up to two years on infected crop residues. Initial crop infection occurs with ideal climatic conditions of up to six hours of moist conditions at temperatures of between 10 and 25ºC. Primary inoculum is derived from airborne or splash dispersed spores, ejected up to 40 cm from stubble of the previous crop.

The formation and dispersal of secondary inoculum known as conidia takes place between 14 – 20 days after primary infection. The spores from these leaf infections are dispersed by rain splash or wind and usually only travel short distances within the crop.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Agar plate test and blotter test.

Treatment/control

- Both SFNB and NFNB can be effectively controlled by an integrated strategy incorporating varietal selection, crop rotation, seed treatment (for NFNB only) and monitoring with a view to fungicide applications if required.

- Varietal selection: Avoid susceptible (S) and very susceptible (VS) varieties. Consult a current Cereal Disease Guide when selecting varieties.

- Crop rotation: Avoid growing barley in successive years in the same paddock as most inoculum survives in stubble. Also, paddocks located close to infected stubble will receive more inoculum than those more distant as the spores are carried by wind. Disease levels will be higher in crops in districts where barley crops are grown in close rotation.

- Seed dressings: Seed dressings are ineffective for the Spot form of Net Blotch. If sowing a susceptible variety harvested from a crop infected by NFNB, treat seed with a seed-applied fungicide registered for NFNB.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Pyrenophora_teres/

http://www.cababstractsplus.org/abstracts/Abstract.aspx?AcNo=20056500364

http://www.inra.fr/hyp3/pathogene/6pyrter.htm

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/smgrains/pp894w.htm

Tan Spot, Yellow Leaf Spot or Blotch

Scientific name

Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (Died.) Drechsler, (1923)

(anamorph. Drechslera tritici-repentis (Died.) Shoemaker)

Other scientific names

P. trichostoma (Fr.) Fuckel

Helminthosporium tritici-repentis Died.

Importance

Seed transmitted. Incidence low.

Significance

It is predominantly a stubble-borne disease. Yield losses caused by Tan Spot can be as high as 30 - 40% but generally range from 3 - 15%.

Symptoms

The initial symptoms are small dark brown spots surrounded by a yellow halo. They appear within five to seven days after infection. Lesions are large (to 1.5 cm) on susceptible Barley cultivars, elliptical, and light tan with a yellow halo. Some varieties have lesions with very large halos, and others show almost no halo. A small dark brown spot in the centre of the tan spot gives the lesions the appearance of an eye. When lesions increase in size, they tend to coalesce, producing larger dead tissue. Eventually, older infected leaves begin to die from the tip. The erect abundant olive-black conidiophores (7-8 x 100-300 .m in size) are formed on the surface of large spots. Conidia are sub-hyaline, cylindrical, mostly 4- to 7-septate and 12-21 x 45-200 .m in size. The basal cell has a form resembling a snake head. The conidia cause secondary cycles of infection during the vegetation season. They are transferred by wind approximately 75 m.

Hosts

P. tritici-repentis affects more than 62 species of fodder and wild cereals of the genera Agropyron, Bromus, Agrostis, Alopecurus, Avena, Hordeum, Lollium, Festuca, Stipa, Androgon, Setaria and Beckmannia.

Geographic distribution

Worldwide.

Biology and transmission

The tan spot fungus grows saprophytically on host debris. In winter it survives on infested straw and barley stubble. In autumn pseudothecia are formed on barley residue. Small black prominent fungal fruiting bodies are often abundant. In early spring these structures produce asci with 8 ascospores. Ascospore are brown, 18-28 x 45-70 .m in size, oval, 3-septate, with median cell having 1 longitudinal septa. Mature ascospores are expelled at a short distance (less than 15 cm) from the fruiting body during spring rains. They germinate and initiate primary infection on young barley leaves. The infection requires a moist period ranging from 6-48 hours. Long-term wetting of the foliage from rain or dew results in development of severe Tan Spot epidemics. The Tan Spot fungus spores germinate and infect barley over a wide range of temperatures provided that the leaves are wet for a long period.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Blotter test.

Treatment/control

- Cultural control: The disease is greatly favoured my minimum tillage systems as the disease survives mainly on crop debris left on the soil surface. Disposal of crop debris by ploughing can help prevent early infection. Many varieties are susceptible.

- Chemical control: Seed infection is controlled by most seed treatments. It is essential to protect the upper leaves from disease by appropriate fungicide sprays when wet weather occurs between GS32 and GS39. Sprays applied against Septoria will normally control Tan Spot although timings are more critical as Tan Spot has a very short latent period (5-7 days). Dithane DG (mancozeb) and Bravo 500 (chlorothalonil) are contact fungicides which control Tan Spot and other barley leaf spot diseases.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.cababstractsplus.org/abstracts/Abstract.aspx?AcNo=20056400494

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Tritici/Tritici_Pyrenophora_tritici-repentis/

http://www.hgca.com/hgca/wde/diseases/TanSpot/Tshost.html/

http://www.agriculture.gov.sk.ca/Default.aspx?DN=62767f83-50f9-4e26-b089-891d7ca991c6

|

|

|

|

Tan/Yellow Leaf Spot (source: HGCA) |

||

Fusarium blight, head blight, scab

Scientific names

Gibberella zeae (Schwein.) Petch [teleomorph]

Fusarium graminearum Schwabe, Group II [anamorph]

G. avenacea R.J. Cook [teleomorph] ; F. avenaceum (Fr.:Fr.) Sacc. [anamorph]

F. culmorum (Wm. G. Sm.) Sacc.

Monographella nivale (Schaffnit) E. Müller [teleomorph] ;

Microdochium nivale (Fr.) Samuels & I.C. Hallett [anamorph] (Pers.) Lagerh

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

Barley quality as well as yield can be substantially reduced by scab infection. Two toxins, zearalenone and deoxynivalenol, are produced in scabby grain. The environment in which cereal is grown determines which species of Fusarium causes head scab. Fusarium graminarium predominates in areas where the climate is warm and where maize and rice are also grown. F. nivale and F. avenaceum cause the disease in cool areas, the latter fungus occurring particularly in association with pasture grass and legumes. F. culmorum predominates in areas intermediate between the extremes, i.e. in moderate to cool areas.

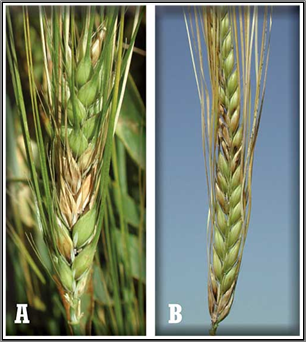

Symptoms

The first symptoms of Fusarium head blight include a tan or brown discoloration at the base of a floret within the spikelets of the head. As the infection progresses, the diseased spikelets become light tan or bleached in appearance. The infection may be limited to one spikelet, but if the fungus invades the rachis the entire head may develop symptoms of the disease. The base of the infected spikelets and portions of the rachis often develop a dark brown colour. When weather conditions have been favourable for pathogen reproduction, the fungus may produce small orange clusters of spores or black reproductive structures called perithecia on the surface of the glumes. Infected kernels are often shriveled, white, and chalky in appearance. In some cases, the diseased kernels may develop a red or pink discoloration.

Fusarium blight Barley (source: NDSU) |

Hosts

Natural: barley, rye, wheat, triticale, maize numerous grasses.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

The fungi causing scab are all members of the genus Fusarium, the asexual spore forming stage. The principal pathogen is Fusarium graminearum, but F. avenaceum and F. culmorum (no known sexual state) have also been reported.

The scab fungi overwinter and survive between crops in infected grain and grass stubble, chaff and cornstalk residue left on the soil surface. They survive as asexual spores (conidia), mycelium and perithecia within which the sexual spores (ascospores) are borne. The fungi are also common contaminants on seed. These fungi continue to grow and produce spores from harvest until the residues decompose in the soil.

The conidia are produced profusely during warm, moist weather on corn and small grain residues. Ascospores produced within perithecia are discharged into the air as the fruiting bodies become wet and dry during fluctuations in moisture levels. Air currents carry these spores to the flowering spikelets. Ascospores and conidia have been collected in the air above barley fields, and both are capable of causing infections. The spores germinate in free water on the surface of the spikelet and invade the flower. Infections are most serious when the anthers are exposed during flowering. Symptoms develop in as little as three days after infection when temperatures range from (25-30°C) and humidity is high. Within seven to ten days after infection, salmon-pink masses of conidia form at the base of the diseased spikelets. These conidia can be blown by the wind to the heads of other cereal or grass plants producing new secondary infections. This process continues to be repeated as long as the spikelets are susceptible and moist weather prevails. Secondary infections may occur from long distance spread of air borne conidia. Ascospores are usually produced on the heads too late in the season to function as secondary inoculum. However, ascospores may persist in crop residues and contaminate seed.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Blotter and Agar Plate Tests.

Treatment/control

- There are few varieties of wheat, oat or barley highly resistant to scab, but in greenhouse tests some varieties restrict the development of the disease to one, or only a few, florets per head. In the field, some varieties appear more resistant than others because they flower earlier or later than other varieties, or because they shed their anthers more quickly than other varieties. These varieties look resistant because they have escaped infection by avoiding rains that supply free water on the surface of the heads for germination of the spores. Differences in susceptibility may also be due to physical barriers to infection of spikelets.

- Plant cereals as far away as possible from old corn fields if stalk residues are left on the soil surface. No-till barley seeded in old corn residues greatly increases the chance of scab. If conventional tillage is used, clean, deep plowing of all infested stubble and straw of cereals and weed grasses, corn stalks and rotted ears is recommended. Complete coverage of crop residues reduces head blight infection by reducing inoculum levels. Manure containing infested straw or corn stalks may harbour the fungus and should not be put on fields planted to small grains. When possible, plant barley following a legume crop (soybean) and maintain a rotation with 2 to 3 years between barley crops. Seed treatment with triadimefon, propiconazole, benomyl or methyl 2- benzimidazoles can reduce scab.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://ohioline.osu.edu/ac-fact/0004.html

http://msuextension.org/publications/AgandNaturalResources/MT200806AG.pdf

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/smgrains/pp804w.htm

Scientific name

Rhynchosporium secalis (Oudem.) J. J. Davis

Synonym: Marssonia secalis Oudem. (1897)

Importance

Seedborne incidence and economic importance moderate.

Significance

Damage is significant, when the disease severity is 20% or higher. Losses of 1-10% are more common. Yield loss is primarily due to reduced kernel weight, but both kernels per head and number of heads per plant may also been affected.

Symptoms

The Scald is characterized by the distinctive lesions forming on coleoptiles, leaves, leaf sheaths, glumes, floral bracts, and awns. Infection appears first as dark or pale gray lesions, which later assume a watery appearance. Later the centers of lesions dry out and bleach, turning light gray, tan, or white, and their edges turn dark brown and can be surrounded with a chlorotic region. The lesions are oval to oblong, not limited by leaf veins. Most lesions occur on the leaf blade and sheath. At floral infections the lesions with dark brown margins and light tan centres arise on the inner surface of floral squama near the awn base. Mycelium is hyaline to light gray, developing sparsely as a compact stroma, and several cells in thickness, under the cuticle of a host plant.

Barley Scald (source: UDEL) |

Hosts

Barley is the only important host, but the fungus can also attack rye and some grasses.

Geographic distribution

Barley Scald is an economically important barley disease in Europe, North America and Australia. It has been reported from South America, Africa, the Middle East, Japan and Korea.

Biology and transmission

Spore production is optimal at 10°C and after 72 hr of wetting. Longer wetting periods than optimal ones lead to death of spores. During alternating wet and dry periods the temperature response curves are similar to those obtained under continuously wet conditions, but few spores are produced. No conidium forms at 30°C. Moisture is also essential for the Rhynchosporium secalis conidia dispersal. Most spores captured in spore traps are caught during or right after rain or overhead irrigation. Splashing water droplets are necessary for the conidia release from sporulating lesions. Mature lesion can produce up to one million spores, which are readily released in water, but the number of airborne spores is relatively small. The disease development depends on local inoculum, because there is no significant long-distance spore dispersal. The optimal temperature for spore production is between 15 and 20°C, and this range is also favourable for infection. The fungus sporulates poorly at temperatures below 5°C or above 30°C. The temperatures from 5 to 30° C are fairly typical of barley growing areas.

Infected host residues and seeds are the sources of primary inoculum. There is no evidence that R. secales survives saprophytically in soil. Mycelial hyphae invade the coleoptile from the pericarp and hull of infected seed as it emerges from the embryo. The fungus sporulates on wet lesions only after leaf tissue becoming necrotic. The wetting time required for maximum spore production decreases as the temperature rises.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Agar plate test.

Treatment/control

- Use resistant cultivars.

- Turn under or deep-till surface barley residue. This reduces disease levels when barley follows barley.

- Seed early with an early maturing variety to miss the major build-up of disease that hits later-sown crops and later maturing varieties.

- Use a crop rotation of at least one year with non-host crops such as other cereals or canola.

- Use resistant cultivars.

- Apply a foliar fungicide. Tilt 250E/Bumper 418EC (propiconazole) and Headline EC (pyraclostrobin) are registered on barley for control of Scald and Net Blotch.

- Baytan 30 (triadimenol) applied as a seed treatment will provide suppression of the seed-borne phase of Scald.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Rhynchosporium_secalis/

http://pnw-ag.wsu.edu/smallgrains/Barleyscald.html

http://www.scri.ac.uk/research/pp/pestanddisease/rhynchosporiumonbarley

http://www.inra.fr/hyp3/pathogene/6rhysec.htm

http://agdev.anr.udel.edu/weeklycropupdate/?tag=barley-yellow-dwarf-virus

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Rhynchosporium_secalis/

Stagonospora Blotch, Septoria Leaf and Glume Blotch

Scientific name

Phaeosphaeria nodurm (E. Muller) Hedjaroude [teleomorph]

Stagonospora nodorum (Berk.) Castellani & E.G.Germano [anamorph] (Berk.) Berk. & Broome

Other scientific name

Septoria nodorum (Berk.) Berk.

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

Septoria nodorum was once the most serious pathogen on cereals. Major losses can occur, through seed shriveling and lower test weights, if these diseases reach severe levels prior to harvest.

Symptoms

The first symptoms appear in the spring as brown spots on leaf blades and leaf sheaths or at the junction of blade and sheath. Later oval red brown spots of 1-2 cm in length develop along leaf veins, having chlorotic margins. The dark brown pycnidia are scattered throughout the lesions. Infected stem nodes turn brown, shrivel and are speckled with dark pycnidia. Pycnidia may develop also on seed surface. In culture, the fungus produces dark violet colonies with pink to white mycelium at the margins. The distinction between wheat and barley biotypes is based on differences in their colony morphology and hosts.

Hosts

Mainly wheat, but occasionally barley and rye.

Geographic distribution

Disease is widely distributed throughout the world.

Biology and transmission

Straw, seed and winter barley plants are sources of primary inoculum. Conidia produced during wet periods are disseminated by splashing rain and initiate infection throughout the growing season. Pycnidia in lesions are followed by pseudothecia in late summer. Ascospores are prevalent during late summer, being predominantly windborne. Germ tubes of both types of spores penetrate barley directly and through stomata. Isolates of barley biotype of S. nodorum are pathogenic only for barley. Infection requires 6 hrs of wetness. Spore germination and infection are optimal at temperatures between 15 and 25°C, but they can occur between 5 and 35°C. Incubation period depends on weather conditions, lasting 10 to 20 days. Wet and windy weather favour epidemics.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Agar plate test.

Treatment/control

- Cultural control: Disposal of crop debris by ploughing can help prevent early infection. A few varieties are particularly susceptible.

- Chemical control: Seed infection can be reduced by a number of seed treatments. It is essential to protect the flag leaf and the ear from disease by appropriate fungicide sprays when wet weather occurs between GS32 and GS59. (GS32 and GS59) are growth stages

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.hgca.com/hgca/wde/diseases/S.nodorum/Snodcont.html

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Septoria_hordei/

http://www.aces.edu/pubs/docs/A/ANR-0903/

|

|

|

|

Stagonospora Blotch (source: HGCA) |

||

Scientific names

Alternaria spp., Cochliobolus sativus, Fusarium spp., Cladosporium spp.

Importance

Seedborne.

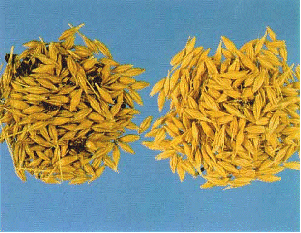

Significance

Losses are due mainly to discounted prices paid for discoloured grain; if Fusarium or Bipolaris are involved, the viability of the seed also may be reduced.

Symptoms

The pericarps of maturing wheat kernels turn dark brown to black, with the discoloration usually destructed to the germ-end of the kernel. If caused by Alternaria spp., the dark colour affects only the pericarp; if caused by Cochliobolus or Fusarium spp., the germ may be invaded and injured or killed. There are other fungi that can cause Black Point, but the three noted here are the most common.

Embryo ends of the grain become chocolate brown to black and, when more severe, more of the grain darken and become shriveled. Germination can be decreased.

Black Point of barley (source: Univ of Adelaide, Australia) |

Hosts

The disease can affect all cereal species although wheat and barley are most commonly affected, the same fungi can cause discoloration of oats.

Wheat is the principal host; triticale and several related grasses also can be affected.

Geographic distribution

Distribution is worldwide, wherever small grain cereals are grown.

Biology and transmission

Usually, kernels are infected by these fungi during the dough stage. If humid weather prevails for a few days to a week just prior to harvest, the incidence of infection will increase and Black Point will develop in many cultivars.

Detection/indexing method in place at the CGIAR Center at ICARDA

- Not important.

Treatment/control

- Resistance, fungicides.

References and further reading

http://www.ag.ndsu.nodak.edu/aginfo/barleypath/barleydiseases/bdhpdf/blackpoint.pdf

http://uispp.icarda.cgiar.org/uispp/barley.doc

http://agwine.adelaide.edu.au/plant/plant_protection/ppp/

http://www.ipmcenters.org/cropprofiles/docs/Graphics/WAbarleySpotBlotch.jpg

Scientific name

Ustilago hordei

Other scientific name

U. jensenii Rostr.

Importance

Seedborne. Moderate economic importance.

Significance

Covered Smut is common. Losses from this disease are directly correlated to the proportion of smutted heads in a field. Estimated average yield losses vary from 1 to 5%.

Symptoms

The smutted heads emerge from the boot (or occasionally through the sheath below the flag leaf) at about the same time or a little later than those of healthy plants. Compact, hard, dark brown to black masses of dusty Smut spores (teliospores) replace the healthy kernels. These masses are covered with a thick, grayish white membrane that may remain more or less intact until the grain matures or is harvested. However, excessive or prolonged wind and rain may rupture the membrane, releasing millions of microscopic teliospores and leaving only the bare spike (rachis) at maturity. Covered Smut usually causes stunting of infected plants, particularly at the top internodes.

Covered Smut of barley (source: agric.wa.gov.au) |

Hosts

Barley, oats, rye and a number of related grasses.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

Some of the Smut spores (teliospores) land on or under the hulls (glumes) of barley kernels in healthy heads. The teliospores on the surface of the seed usually remain dormant, while those deposited under the glumes may send infection hyphae beneath the hulls before or after threshing. The barley plant becomes infected between the time the seed germinates and the seedling emerges from the soil. Infection occurs over a temperature range of (14° to 25°C) with an optimum of (20° to 24°C).

Germinating teliospores develop a promycelium and four primary sporidia from which abundant secondary sporidia are produced. The sporidia are of two mating types and seedling infection occurs via direct penetration of the young shoot (coleoptile) by infection hyphae produced by the fusion of sporidia (basidiospores). The fungus continues to grow systemically within the plant tissues; and, at maturity, replaces the kernels with a dark mass of teliospores. There is only one infection cycle per year. The amount of disease in the new barley crop depends on the percentage of infested kernels that were planted and on the temperature and moisture of the soil during germination. The highest percentages of smutted plants occur in acid or neutral soils when the soil temperatures during this period are between (10° to 21°C) and the soil moisture is low to moderate. This is probably the reason Covered Smut is more prevalent in winter barley than in spring barley. Soil type, soil compaction, depth of seeding and the rate of seedling growth may also affect the development of Covered Smut. The causal fungus can be subdivided into a number of physiologic races based on their different abilities to attack a series of differential barley varieties.

Covered Smut of barley |

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Centrifuge wash test.

Treatment/Control

- Use resistant cultivars.

- Avoid continuous cropping of winter wheat and do not seed winter wheat within 2 km of a known Bunt infected field of either spring or winter wheat because the spores are windborne.

- Use a hot water seed treatment for loose Smut. Dip seeds in water at 20oC for five hours, drain and then dip in water at 49 oC for one minute, then water at 52oC for exactly eleven minutes, then immediately in cold water until seeds cool off. Some seed may be killed by hot water treatment.

- Use systemic seed treatments that contain carbathiin for loose smut control in wheat and barley. All other semi-loose, Covered Smut and Bunts in cereals are controlled by any of the registered fungicide or fungicide combinations.

- Treat the seed with a recommended seed treatment (Alphaflo, Dynaflo, Foliarflo-C, Vitaflo C, Vitavax 200FF).

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed washing, seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Ustilago_hordei/

http://web.aces.uiuc.edu/vista/pdf_pubs/100.pdf

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$Department/deptdocs.nsf/All/prm2431?OpenDocument#common

http://www.agronort.com/novedades/trat_semi_tri/index.html

http://www.agric.wa.gov.au/PC_92925.html

Scientific name

Claviceps purpurea (Fr.) Tul

Importance

Infestation of seedlots. Moderate economic importance.

Significance

The disease is of greater significance because of the toxic alkaloids produced by the fungus. Modern cleaning methods remove ergots from grain before it is milled or used for animal feed, but the process is costly and may leave toxic residues. The legal limit of Ergot is 0.3 per cent by weight for rye or wheat and 0.1 per cent for barley, oats or triticale. Grain is classified as "ergoty" if it exceeds this level and is of lower value. Ergot toxins are not destroyed by baking.

Symptoms

The most common sign of Ergot is the dark purple to black sclerotia (Ergot bodies) found replacing the grain in the heads of cereals and grasses just prior to harvest. The Ergot bodies consist of a mass of vegetative strands of the fungus. The interior of the sclerotia is white or tannish-white. In some grains, ergot bodies are larger than the normal grain kernels, while in other grains, such as wheats, grain kernels and the Ergot bodies may be similar in size. A larger size separation between the sclerotia and the grain kernel simplifies the removal of Ergot bodies during grain cleaning.

Prior to development of the sclerotia bodies, the fungus develops a stage in the open floret (flowering head part) commonly called "honey dew", which consists of sticky, yellowish, sugary excretions of the fungus which form droplets on the infected flower parts.

Ergot (source: www.agric.gov.ab.ca) |

Hosts

Ergot has a wide host range of about 60 genera, all in the grass family. Rye and triticale are particularly susceptible because they are open-pollinated, but wheat, barley and many grasses (including weed grasses such as quack grass, meadow foxtail, wild oat, cheatgrass, hair grass, wild barley, annual bluegrass and green foxtail) are also among the hosts.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

Sclerotia produced in small grain fields or grassy areas fall to the ground and survive on the surface of the soil. In the spring and early summer, the sclerotia germinate to produce tiny mushroom-like bodies approximately the size of a pin. Spores (ascospores) formed by a sexual process in these bodies are shot into the air, and wind currents may carry them to grain heads.

The first infections are from these windborne sexual spores. The spores land on open flowers, germinate and the fungus then invades the embryo of the developing kernel. Soon a yellow-white, sweet, sticky fluid (honey-dew) exudes from the infected flowers. The fluid contains a large number of asexually produced fungus spores (conidia). Many species of insects visit the honey-dew and become contaminated with the fungus spores. These insects visit other grass flowers and spread the fungus, in a repeating cycle that continues as long as the florets are open. Spores may also be transferred to other grain heads by rain-splash and direct contact. Once the fungus becomes established in the florets, it grows throughout the embryos and replaces them, later producing the dark sclerotia. Many sclerotia fall to the ground before harvest and overwinter on the soil surface, serving as potential sources of spores the following year.

Ergot (source: www.agric.gov.ab.ca) |

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Visual inspection.

Treatment/control

- Use healthy clean and certified seed.

- Deep-ploughing (12-15 cm depth) at the level of the stubble roots.

- Rotate to nonhost crops.

- Burn stubble.

- Provide adequate nitrogen but avoid excessive fertilization.

- Avoid boron deficiency.

- Seed treatments. Fuberidazole + triadimenol.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Destroy the seed lot.

References and further reading

http://pnw-ag.wsu.edu/smallgrains/Ergot.html

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/plantsci/crops/pp551w.htm

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm7770

Scientific name

Tilletia controversa Kühn

Importance

High phytosanitary importance.

Significance

Considerable yield losses can occur when susceptible cultivars are grown or chemical seed treatments are not used. The disease is prevalent in areas with temperatures just above freezing for several months of the year and snow cover. In West Asia and North Africa it occurs only at altitudes above 1100 m. Bunted spikes result only from high levels of seed infestation (more than 20 000 teliospores per seed).

Dwarf Bunt is a serious disease, particularly of winter wheat at relatively high altitudes. It is very difficult to control because of resistant resting spores, which remain viable in the soil for a number of years and because most seed-applied fungicides are not effective.

Symptoms

Affected plants are stunted to various extents. Tillering may be increased. Kernel symptoms resemble those of Common Bunt. The main symptoms are fungal structures called “bunt balls,” which resemble kernels but are completely filled with black teliospores. The bunt balls of dwarf bunt are more spherical than those of common bunt. When bunt balls are crushed they give off a fetid or fishy odour. Infected spikes tend to be bluish green in colour (or darker), and the glumes tend to spread apart slightly; the bunt balls often become visible after the soft dough stage.

Bunt is not very conspicuous in the field, because bunt balls are hidden inside the heads, and infected, dwarfed tillers may be hidden in a canopy of taller, healthy heads. Bunt balls are often large enough to push the glumes apart, causing the infected heads to have a ragged appearance. Awns are sometimes malformed. Diseased heads become easier to see as the crop matures and bunt balls begin to break open, revealing the black powdery spores. Dark spore clouds may be produced at harvest when infection levels are high.

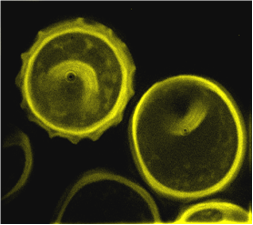

Fluorescence microscopy: one spore of T. controversa (left) compared to a spore of T. laevis (right) (source: CIMMYT) |

Hosts

Wheat, rye, triticale (less commonly), barley and a number of grasses (Aegilops spp., Agropyron spp., Alopecurus myosuroides, Arrhenatherum elatius, Bromus spp. Dactylis glomerata, Elymus spp., Festuca spp., Koeleria cristata, Lolium spp., Poa spp.). Spring wheat is not affected.

Geographic distribution

Dwarf bunt can occur worldwide. It is limited to temperate climates in areas where winter cereals are grown with prolonged snow cover, including parts of Europe, the USA, Canada, the Near East.

Biology and transmission

The pathogen is both soilborne and externally seedborne, with the majority of dwarf bunt infections resulting from soil infestation. Teliospores can remain viable for 3 to 10 years in soil or on seeds.

Dwarf bunt spores require low temperatures (optimum 0-8°C) over a period of several weeks to germinate. This normally occurs under snow cover on unfrozen ground during the winter months.

Dwarf bunt survives for long periods in the soil (over ten years). The disease may be spread on seed, and also at harvest when spores contaminate the soil and may be blown to neighboring fields. Cultivation equipment could also spread contaminated soil from field to field.

When winter wheat is planted in infested soil, the crop may become infected over the winter months. Dwarf bunt spores germinate only at low temperatures (optimum 3-8°C) over a period of several weeks. This normally happens under snow cover on unfrozen ground, between December and February. Conditions are not favourable for dwarf bunt every winter, which explains why the disease is not a problem every year.

When plant growth resumes in the spring, the fungus grows systemically within the infected plants. Heads are colonized by the fungus as they develop, and bunt balls are formed instead of kernels.

Detection/indexing methods used at ICARDA

- Dry visual inspection.

- Centrifuge wash test.

Treatment/control

- Seed can be treated with systemic fungicides such as Difenoconazole or NaOCl (0.13 M at maximum 55°C).

- Soilborne inoculum is generally difficult to control; spores of the fungus can survive for more than 10 years in the soil.

Procedure followed at ICARDA in case of positive test

- The pathogen is quarantine A1 listed. The seed lot is destroyed.

References and further reading

Diekmann M, Putter CAJ, editors. 1995. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Germplasm. No. 14: Small Grain Temperate Cereals. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), Rome, Italy. pp. 26-27. Available here.

Mathre DE. 1982. Compendium of barley diseases. American Phytopathological Soc.78p.

Peterson GL, Whitaker TB, Stefanski RJ, Podleckis EV, Phillips JG, Wu JS, Martinez WH. 2009. A Risk Assessment Model for Importation of United States Milling Wheat Containing Tilletia contraversa. Plant Disease. 93: 560-573.

Sitton JW, Line RF, Waldher JT, Goates BJ. 1993. Difenoconazole seed treatment for control of dwarf bunt of winter wheat. Plant Disease 77:1148-1151.

Stockwell VO, Trione EJ. 1986. Distinguishing teliospores of Tilletia controversa from those of T. caries by fluorescence microscopy. Plant Disease 70:924-926.

Warham EJ, Butler LD, Sutton BC. 1996. Seed Testing of Maize and Wheat: A Laboratory Guide. Mexico, D.F.: CIMMYT. p. 60.

Xue AG, Tenuta A, Tian XL, Sparry E, Etienne M, Gaudet DA, Menzies JG, Graf RJ, Falk DE, Smid A, Pandeya RS. 2007. Evaluation of winter wheat genotypes and seed treatments for control of dwarf bunt in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Plant Patholology 29:243-250.

Common Root Rot, Crown Rot, Seedling Blight

Scientific names

Fusarium culmorum (Wm. G. Smith) Sacc.

F. graminearum Schwabe : Gibberella zeae (Schwein.) Petch[teleomorph]

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

These fungi can cause significant yield and quality losses.

Symptoms

There are many species of Fusarium that affect cereals. These fungi form a complex of diseases on seeds, seedlings and adult plants. The seedborne pathogen Microdochium nivale (formally known as Fusarium nivale) may also be included in this group of fungi.

Fusarium lesions often begin in the leaf sheath at the stem base where crown roots split the leaf sheath when emerging. This infection can then spread up the leaf sheath causing long dark brown streaks at the stem base. The most commonly seen symptom is the dark brown staining of the lower nodes. On older plants Fusarium infection can produce a true foot rot, where the stem base becomes brown and rotten, resulting in lodging and white-heads. This symptom is less common, although it can be found in very dry seasons.

Hosts

The disease affects wheat, barley, oats triticale and grasses.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

Inoculum occurs freely in soil and in host debris and seeds of wheat and barley. Conidia germinate in the presence of susceptible hosts and initiate the primary infection on coleoptile or primary roots. Most of conidia are found in the top 15 cm layer of soil. Environmental factors affect greatly the severity of the Common Root Rot. Warm soil at temperatures 20-30oC favours the fungus growth. Losses are probably the most severe in years of lowered rainfall, when plants are stressed for water, or in years with extreme temperatures.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Blotter test, Agar Plate Test.

Treatment/control

- All of the current recommended seed treatment fungicides are effective. While seed treatment greatly reduces the risks of seedling blight it will not afford adequate protection against later invasion by Fusarium species present in the soil.

- Fungicides such as prothioconazole and boscalid, applied for the control of other diseases, can give good control of stem base Fusarium infection.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment, cultural practices, resistance.

References and further reading

http://www.hgca.com/hgca/wde/diseases/Fusarium/Fushost.html

http://hgca.com/minisite_manager.output/

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Fusarium_sp/

|

|

|

|

Root Rot: Fusarium infection of emerging seedlings and root necrosis (photos: www.agroatlas.ru) |

||

Scientific name

Cephalosporium gramineum Nisikado & Ikata in Nisikado et al.

Other scientific name

Hymenula cerealis Ellis & Everh.

Importance

Low

Significance

The disease is common but at very low levels and does not cause economic losses.

Symptoms

Affected plants are usually randomly scattered through the crop. Affected tillers usually have a single distinct bright yellow stripe on each leaf which extends onto the leaf sheath. All leaves on a tiller usually show symptoms but not necessarily all tillers on a plant. The vascular tissue close to the nodes is frequently discoloured.Tillers can ripen prematurely and produce white-heads.

Hosts

The disease affects wheat, barley, oats, rye and triticale.

Geographic distribution

Africa [South Africa (Transvaal)]; Europe (Germany, UK, Netherlands, Italy); Asia (Japan); and N. America [USA (Washington State, Montana].

Biology and transmission

The casual fungus is a slow growing fungus in the soil but it is favoured by wet soil conditions and continuous cereal cropping. The soilborne fungus enters plants via the roots during winter and in early spring. There is evidence that the fungus can be transmitted by seed. Once inside the plant, the fungus moves up the plant causing blockage at the nodes, distinctive leaf symptoms and stunting. At harvest the fungus returns to the soil in the trash. Removing straw, ploughing and, where permitted, burning are the most effective ways to prevent a build up of the problem. If straw removal is not practical, then deeper ploughing to remove the straw from the root zone may help.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Blotter test.

Treatment

The disease does not warrant cultural control measures. The incidence of the disease can be reduced by crop rotation and wheat, in conventional rotations, is rarely, if ever, badly affected. The fungus most likely survives on grass weeds so elimination of such weeds is also likely to reduce disease incidence. The fungus also survives mainly in the top 10 cm of the soil so ploughing will also help to remove inoculum.

Procedure followed in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.sac.ac.uk/mainrep/pdfs/tn618cephalosporium.pdf

http://www.hgca.com/minisite_manager.output

http://ohioline.osu.edu/b827/0004.html

Distinct bright yellow stripe on leaves (photo: www.hgca.com) |

Chlorotic and interveinal stripes on leaves (photo: ohioline.osu.edu) |

Scientific names

Cochliobolus sativus (S. Ito & Kurib.) Drechsler ex Dastur (1942) [Teleomorph]

Bipolaris sorokiniana (Sacc.) Shoemaker (1959) [anamorph]

Other scientific names

Drechslera sorokiniana (Sacc.) Subram. & B.L. Jain (1966)

Helminthosporium sativum Pammel, C.M. King & Bakke (1910)

Importance

Seedborne

Significance

Spot Blotch can cause severe losses under optimum condtions.

Symptoms

Initially, small brown spots occur on leaves. These expand to larger dark brown blotches. The blotches may be surrounded by a yellow zone. Blotches may coalesce resulting in premature leaf death. The fungus causing Spot Blotch also causes Seedling Blight, Common Root Rot and Kernel Smudge (Black Point).

Hosts

Blotch affects wheat, triticale, barley and most grasses.

Geographic distribution

It is found worldwide, but is especially prevalent in more humid and higher rainfall areas.

Biology and transmission

Straw, seed, soil, winter barley and wild grasses are sources of primary inoculum. Besides causing Spot Blotch, this pathogen can attack roots, heads and grain. The symptoms of Spot Blotch vary with the host genotype and growth stage, as well as the environment. The first symptoms appear in the spring as rounded brown spots 2 x 5 mm with large yellow halos. Spots can develop on leaves and leaf sheaths at all stages of plant development. The lesions are typically round to oblong, up to 2-5 x 15-20 mm restricted in width by leaf veins, dark brown and chlorotic at their margins. In some cases, lesions may continue to enlarge and coalesce to form blotches that cover large areas of leaves. The kernel blight phase of this disease may develop if inoculum is available and the environmental conditions are conducive to infection. The mycelium of B. sorokiniana is deep olive brown. Fungus produces toxins (the main toxin being helminthosporol), which are capable of causing disease symptoms. The sexual state is rare in nature. Pseudothecia can be produced in the laboratory by inoculating boiled barley kernels on mineral salt agar with a suspension of compatible mating types.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Freezing blotter test.

Treatment/control

- Use clean seed and seed treatment to reduce the potential for poor germination, Seedling Blight and early season Root Rot. Residues into the soil may help to reduce disease risk.

- Use a crop rotation of at least two years between cereal crops or grasses. Rotation will help to reduce the amount of infested residue as well as the level of soilborne inoculum.

- If weather conditions are favourable and Spot Blotch symptoms are readily present at flag leaf emergence, a fungicide application may be considered. Propiconazole is registered for Spot Blotch of barley.

- Breeders and pathologists are starting to look more at the development of Spot Blotch resistant varieties, but their commercial availability is likely to be several years away.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatment.

References and further reading

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Bipolaris_sorokiniana/

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm2432

Spot Blotch symptoms on leaves of barley (photo: www1.agric.gov.ab.ca) |

Barley head showing symptoms of Spot Blotch infection (photo: www1.agric.gov.ab.ca) |

Speckled Leaf Blotch, Septoria Leaf Blotch

Scientific name

Septoria passerinii Sacc., (1884)

Other scientific name

Septoria murina

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

The disease is economically very important in many barley producing areas of the world, particularly where high rainfall occurs and there is a wet climate.

Symptoms

Speckled Leaf Blotch symptoms first appear in autumn. The initial symptoms are small yellow spots on the leaves. These spots expand and later turn light tan. Lesions are irregularly shaped and range from elliptical to very long and narrow. Lesions contain very small round black speckles that appear like grains of black pepper. The black speckles are fungal fruiting bodies. The black fruiting bodies can usually be seen without the aid of a magnifying glass.

The disease begins on the lower leaves and gradually progresses up to the flag leaf. Leaf sheaths are also susceptible to attack. In wet years, the Speckled Leaf Blotch fungus can move to the heads and cause Glume Blotch symptoms. Brown lesions appear randomly on the glumes and awns. These lesions bleach to light tan and often contain the typical black speckles that are the fruiting bodies of Septoria. The fungal fruiting bodies are often seen embedded in the lesions on the awns. The Glume Blotch phase appears to cause significant yield loss, but this is difficult to measure.

Speckled Leaf Blotch can be confused with Tan Spot and Nodorum Leaf Blotch. Tan spot causes elliptical tan lesions with a yellow halo. However, Tan Spot does not have the obvious black fungal fruiting bodies that characterize speckled leaf blotch. Speckled Leaf Blotch is sometimes confused with Nodorum Leaf Blotch caused by Stagonospora nodorum. Under moist conditions, Nodorum Leaf Blotch produces very small light brown speckles in the lesions which could be mistaken for the black speckles produced by speckled leaf blotch. The speckles of Nodorum Leaf Blotch are smaller and more difficult to see than with Speckled Leaf Blotch caused by Septoria tritici. Nodorum Leaf Blotch often fails to form speckles. In that case, it looks very similar to Tan Spot. Both Septoria tritici and Stagonospora nodorum cause Glume Blotch. Separating these two types of Glume Blotch usually requires laboratory examination. Knowing the species is not important for fungicide decisions because both respond equally to fungicides.

Hosts

Current barley varieties are susceptible.

Geographic distribution

Wherever barley is produced, but disease is most severe in cool, wet climates.

Biology and transmission

The fungi overwinter on seeds and on stubble, straw and leaves of winter wheat. Spores infect the new crop during wet weather. Secondary infection to nearby plants results from spores produced on infected leaf spots transported by splashing rain and wind.

Wet windy weather favours this disease, while dry conditions reduce or prevent new infections and spore production on diseased plants. Plants must remain wet for six hours or more for successful spore infection. Increases in the incidence of this disease are related to denser, more humid foliage that occurs with higher nitrogen inputs.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- No significant importance, Agar plate test.

Treatment/control

- Use a crop rotation with non-cereal crops.

- Turn under the stubble and crop residue to reduce disease incidence and control volunteer wheat seedlings.

- Use seed grown in the drier areas of the province. It may be free of this disease or very low in seedborne infection.

- Do not use stubble mulching and minimum till. These practices increase the incidence of this disease.

- Use wide row spacing and adequate but not excessive nitrogen levels. These practices lower canopy density and humidity, which favour infection.

- Use resistant cultivars.

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centers in case of positive test

- Seed treatment to produce clean, healthy seed.

References and further reading

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm7770

http://www.ag.ndsu.nodak.edu/aginfo/barleypath/barleydiseases/bdhpdf/speckledleafblotch.pdf

Loose Smut, Semiloose, False Loose Smut

Scientific names

Ustilago nuda (C.N. Jensen) Rostr., (1889) & Ustilago avenae (Pers.) Rostr

Other scientific names

Ustilago segetum var.nudaC.N. Jensen, (1888)

Ustilago nuda f.sp hordei Schaffnit, (1928)

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

This disease occurs throughout the world and reduces yields proportionate to the incidence of smutted heads. The disease does not cause complete yield loss, but losses as high as 27% have been reported and, more commonly, losses of 15% are recorded.

Symptoms

Loose Smut symptoms are obvious between heading and maturity. Barley heads are black to dark brown. Some diseased heads may be taller than any of their healthy neighbours. Most affected heads emerge slightly earlier than the normal ones and their spikelets may be entirely transformed into a dry, olive brown spore mass. The thin membrane ruptures shortly after the heads emerge and spores are dispersed by wind. Within a few days only the rachis remains, although awns may remain on heads. Infected seeds are fully germinable and not visibly altered. U. nuda fungus produces a hyaline, dikariotic mycelium in host tissue. At maturity, the hyphae of the mycelium thicken and fragment into teliospores, which are olive brown, globose to ovoid, spiny and 3.6-9 microns (most often 5.5-6 microns) in diameter. The teliospore germinates to form a basidium. Compatible basidial cells or short hyphae produced by the former fuse to form infectious dikaryotic mycelium. U. nuda overwinters as dormant mycelium only within the embryo of infected barley seeds. When infected seeds germinate, the fungus is carried along with the growing point and ramifies in the shoot apex, culm nodes and seed primordia. Usually all head tissues except rachis are invaded and converted into sori covered with delicate pericarp membrane. During the formation of the sori the hyphae differentiate and fragment into teliospores. The sorus membrane breaks down shortly after the heads emerge and frees the teliospores for dispersal. They land in open flowers and cause infection by growing through the ovary wall. The dikaryotic infection hyphae proceed between and through the cells to the developing embryo and become established in the tissue of the scutellum, embryo axis and growing point. Teliospores are dispersed by wind. Although long-distance spread is possible, most infections probably occur only during flowering.

Hosts

Barley, wheat, oats and triticale.

Geographic distribution

Cosmopolitan.

Biology and transmission

The Loose Smut Fungus survives as a dormant fungal thread inside the embryo of barley seed. The pathogen is activated when the infected seed germinates and it extends toward the growing point of the plant.

Evident from flowering onwards when the plant begins to form the head, the fungus invades all of the young head tissue except for that of the rachis (production of plant growth hormones by the fungus results in infected plant heads reaching flowering earlier than healthy heads).

The head produced by the infected plant contains black spore masses in place of the grain. The spores are loosely held and are easily spread by wind onto neighbouring healthy plants. Because flowering of infected heads occurs earlier than healthy heads, production and release of spores occurs when the rest of the crop is flowering. Spores are blown by the wind into the flowers of the healthy plants. The spores enter the ovaries and become part of the developing grain. In this way, seed for the following year becomes infected.

Disease favours wet, cloudy weather and moderate temperatures (16-22°C). These conditions promote longer and more open flowering for the host. A single heavy rain during flowering in affected fields can cause a tenfold increase in infection.

Detection/indexing method in place at ICARDA

- Embryo test.

Treatment/control

- Losses due to Nuda Loose Smut can best be avoided by sowing certified Smut-free seed.

- If such seed is not available, seed treatment by a systemic fungicide is the best alternative.

- Nuda Loose Smut cannot be controlled by protectant chemical seed treatments, because the fungus is carried in the embryo or seed germ.

- Treat the seed with a recommended seed treatment (Alphaflo, Dynaflo, Foliarflo-C, Vitaflo C, Vitavax 200FF).

Procedure followed at the CGIAR Centres in case of positive test

- Seed treatments.

References and further reading

http://www.agroatlas.ru/en/content/diseases/Hordei/Hordei_Ustilago_nuda/

http://www.hannafords.com/disease.php?id=9

http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm2431

http://www.biology.ed.ac.uk/research/groups/jdeacon/FungalBiology/grassmut.htm

http://agdev.anr.udel.edu/weeklycropupdate/?tag=barley-yellow-dwarf-virus

|

|

|

|

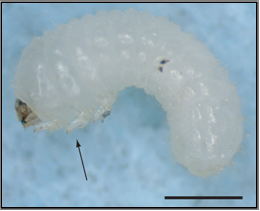

Dark brown spore masses (photos: ICARDA) |

||

Insects - barley

Contributors to this section: ICARDA, Syria (Siham Asaad, Abdulrahman Moukahal).

|

Contents: |

Scientific name

Trogoderma granarium Everts, 1898

Other scientific name

Trogoderma affrum Priesner, 1951

Importance

Seedborne.

Significance

The Khapra beetle is considered to be the most serious pest of stored products under hot dry conditions. Complete destruction of grain and pulses may occur in a very short time. In humid climates, the rates of increase of its competitors are so much greater that it has difficulty in establishing itself. However, in such areas, it lives at the inner edge of the expanding hot zone of stacks or bulks, in which heating has been induced by the activity of other species. In the EPPO region in the 1970s, T. granarium was rated as of considerable economic importance in Cyprus, Tunisia and Turkey.

Symptoms/damage

This pest causes loss of stored grain and consumes and breaks-up kernels. Young larvae feed on damaged seed, older larvae feed on whole grains. The larvae attack the embryo point or a weak place in the pericarp of grain or seed, and can cause significant weight loss when left undisturbed in stored grain, weight loss between 5-30%, in extreme cases of 70%, which may lead to significant reduction in seed viability. Severe infestation may cause unfavourable changes in chemical composition, can damage dry commodities of animal origin, large numbers of larval skins and setae may cause dermatitis and/or allergic reactions, contaminate grain with body parts and setae which are known to cause gastrointestinal irritation. Larvae move in and out of sacked material, weakening the sacks.

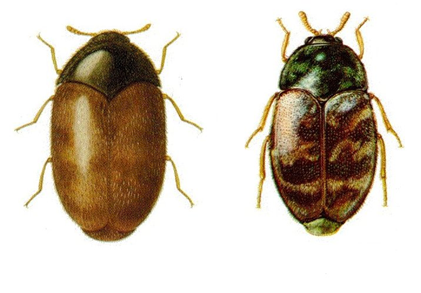

Khapra Beetle (from: agspsrv34.agric.wa.gov.au) |

Hosts

T. granarium is a general storage pest which occurs mainly on cereals and cereal products, oilseeds (especially groundnuts and oilcakes), pulses and pulse products, as well as on compound animal feed. The occurrence on other products, as on empty sacks and gums, etc., is probably accidental by cross infestation.

Geographic distribution

Worldwide.

Biology and transmission

The adults are short-lived, mated females living 4-7 days, unmated females 20-30 days and males 7-12 days; they do not fly and feed very little, if at all. Mating occurs about 5 days after emergence. The beetle can lay a full complement of eggs following a single mating, but a second mating greatly increases the total number of eggs produced: once-mated females lay 66 eggs, whereas twice-mated individuals lay about 58 and then 509 eggs after the respective matings. Delay in mating of 15-20 days results in up to 25% reduction in fecundity. The preoviposition period, which is not affected by humidity, is negligible at 40°C, 1 day at 35°C, 2 days at 30°C, 2-3 days at 25°C, and, at 20°C, no eggs are produced. Under optimum conditions, the female lays an average of about 50-90 eggs loosely in the host material. The eggs hatch within 3-14 days.

Complete development takes place within the heat range of 21 to over 40°C. The life cycle from egg to adult takes an average of 220 days at 21°C, 39-45 days at 30°C and 75% RH and 26 days at 35°C, the optimum. Development can take place at a relative humidity as low as 2%, at which the life cycle is prolonged.

The rate of increase of populations at 33-37°C is about 12.5 times per month: this compares with 20 times at 32-35°C (minimum RH 30%) for Rhyzopertha dominica and 25 times at 27-31°C (minimum RH 50%) for Sitophilus oryzae, the principal competitors of T. granarium as pests of whole grain.